She’s all okay

Darien Brahms is better than ever on Number 4

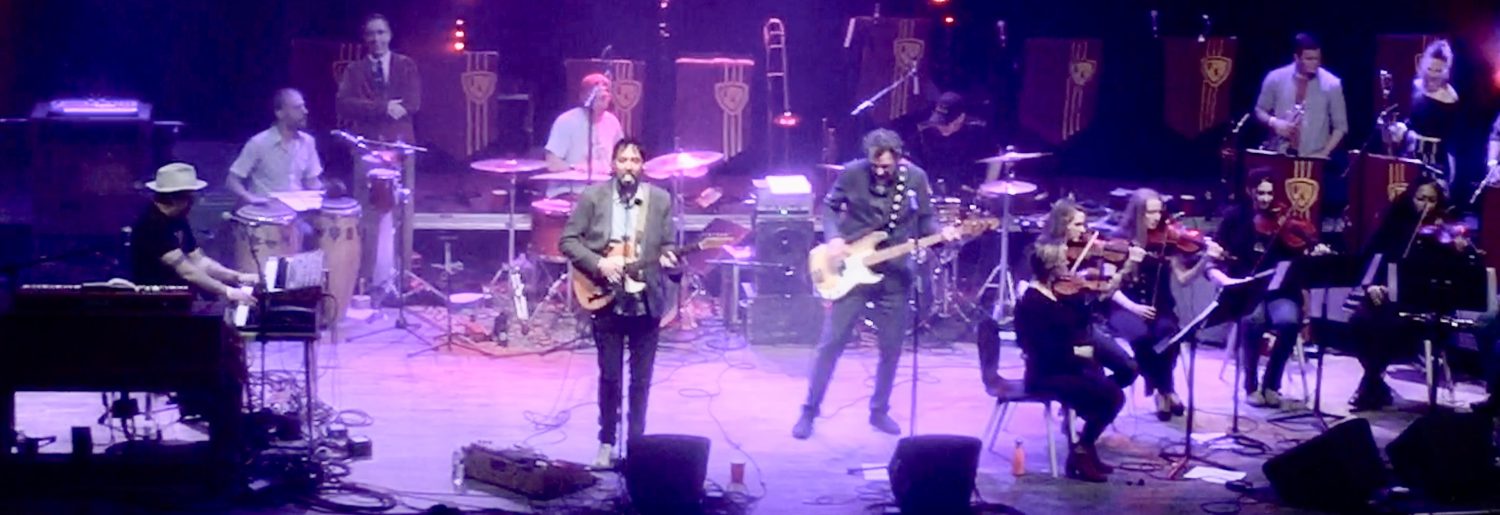

With one of the longest continuous careers in Portland music, Darien Brahms has been many things to many people. She was my first real local-music crush when I moved here in 1999 [this review originally ran in 2008; image is from 2012], after I first saw her frontgal, lounge-jazz strip-tease act at the Skinny with the Munjoy Hill Society. I know I’m not the only one who’s been captivated by her as chanteuse.

She’s been pegged, too, as an alt-country diva or anti-war activist, but on her solo records she’s mostly been an old-school rocker, who loves her guitar and knows how to spin a chorus. So, five years after the spectacular Green Valentine, it should be no surprise Brahms leads Number 4 with the most down and dirty tune that’s been rumbling around in her head.

She’s been pegged, too, as an alt-country diva or anti-war activist, but on her solo records she’s mostly been an old-school rocker, who loves her guitar and knows how to spin a chorus. So, five years after the spectacular Green Valentine, it should be no surprise Brahms leads Number 4 with the most down and dirty tune that’s been rumbling around in her head.

“Cream Machine” is maybe the best blues song I’ve heard since the last Black Keys record, a cycling and dirty riff supported by a Bayou rattle and panting breaths. Her promise that “I won’t be your cream machine” is deliciously profane; she even purrs like a jaguar. I’m a little bit frightened. Sneering slide guitar tells you, “don’t even bother baby … chocolate (grunt) cream/ Cinnamon steam/ I know you can be sweet to me, baby.” A throaty organ from Jack Vreeland enters for the bridge, by which point you ought to be completely enthralled.

Cartwright Thompson’s pedal steel (Brahms gets a fair amount of help on this record. Guess she plays a good host at her home studio) next provides the underpinning for a dark and lumbering menace of a song, “Shut up and Be Quiet.“ Here’s the first of some nice poetry on the record, too: “Coded whispers fill the room of my unfurnished body/ Secret message, a new voice you finally gave/ And it’s not just another vacant figure of speech.”

On “For Crying out Loud,” we get this gem: “Does she suffer from too much religion/ Or every former lover’s final decision?” Paul Chamberlain’s bass is high in the mix here and lyrical, but it’s not nearly his best contribution. He also served as the packaging designer, and I’ve got to say that the CD booklet that comes with Number 4’s jewel case is the best I’ve ever seen from a Portland band, and right up there with anything nationally or internationally. It’s like he graphically depicted every one of Brahms’s rough edges and toothy smiles.

There’s a fair amount of Brahms history, here, actually, including the soothing and sanguine “We’re All Okay,” with just Brahms on guitars and multiple vocal tracks, from 2001’s GFAC 207, Vol. 2. And I’ve got to assume the instrumental “Slide Song 1993” is what it says it is. Actually, with the tape hiss and metallic whine, it’s hard to tell it’s a guitar at some points; often it sounds more like a humpback whale’s mating call. In a good way.

I think the single here is “Sweet Little Darling,” which opens with a toy piano and Ginger Cote’s bass drum building in. Though she’s often aggressive or languid, Brahms here is in baby doll mode, a great ’60s rock pop take, with a cool electric guitar move in the chorus: “You’re my sweet little darling, sweet little darling, sweet little darling, yeah.” It’s delectable and irresistible, so pretty and electric in its appeal. Dave Noyes on the cello late is a great move forward, joining himself in the finish with the melodica, one instrument in each channel.

I guess after five years of work, it shouldn’t be surprising that the album is both dense and expertly organized, with a fun-with-samples take in the middle for disconcerting comic relief in “Kitty’s Trapped in the Well,” and a special “bonus track” you might remember from the last presidential season: “Too Late for Whitey.” There’s variety here in genre, but the nakedly raw emotion is just about universal.

In the Rolling Stones rocker “I’m So Afraid,” Brahms is as honest and bare as any kindergartener, a naked accounting of fears: “I’m so afraid of losing my job/ I’m so afraid of being robbed/ Being raped/ No escape/ Being bored/ And flipping out on the Doors/ Love me two times baby.” It’s compressed into a perfect 1:59 track that finishes with this admission: “I’m so afraid of God falling down … I’m shaking baby and it’s not from love/ It’s from fear.”

The horse whinny at the finish is strangely appropriate.

Even if Brahms was never really that Little Bundle of Sugar (2000), it’s never been hard to be sweet on her. Now she’s let us closer than ever before and she’s never seemed sweeter. Though maybe she’s a hard candy.

And she probably wants to punch me in the face for that “sweet” nonsense.