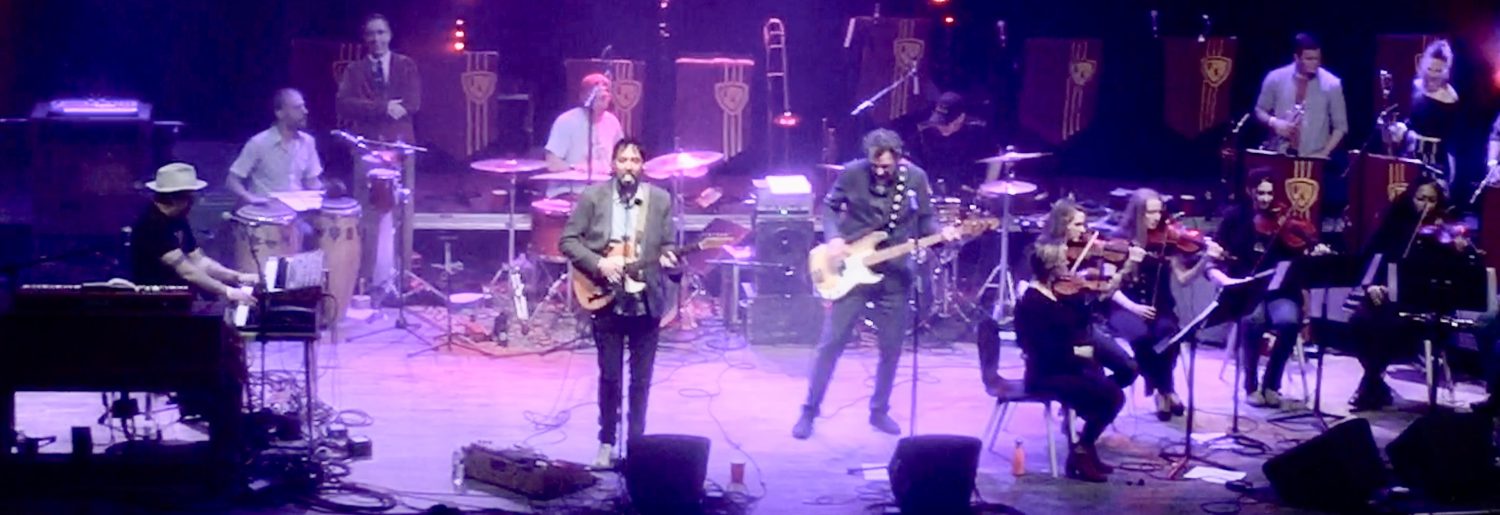

On the road again

Steve Grover makes a Statement

Everyone wants to be in Steve Grover’s band. Well, every massively talented jazz musician, anyway. I can’t imagine something more enjoyable than being set up to succeed in the way a musician is with one of Grover’s jazz compositions — given both exquisite structure and open-aired freedom.

On his newest Statement [*this originally published in December of 2011], a nine-song, all-original work of instrumental jazz that sits somewhere in the Getz-Parker pocket, Grover has with him his quintet of Chris Van Voorst Van Beest on stand-up bass, Tony Gaboury on guitar, Trent Austin on trumpet, and David Wells on tenor sax. Plus, he adds Jason St. Pierre on alto sax for four tracks. The result is a record that’s genuinely in a different class than most of what you hear locally.

On his newest Statement [*this originally published in December of 2011], a nine-song, all-original work of instrumental jazz that sits somewhere in the Getz-Parker pocket, Grover has with him his quintet of Chris Van Voorst Van Beest on stand-up bass, Tony Gaboury on guitar, Trent Austin on trumpet, and David Wells on tenor sax. Plus, he adds Jason St. Pierre on alto sax for four tracks. The result is a record that’s genuinely in a different class than most of what you hear locally.

My personal favorite moments are when the saxophones get together in opposing channels, as on the opening “Changing Course” and the closing “Do What You Want” (one of two songs inspired by Jack Kerouac [*He’d explore Kerouac more later.]). Wells and St. Pierre are both subtle and dexterous in their playing, taking their instruments outside of the brute-force displays you so often see with saxophones and making them dance with each other. The flutter-out of their break in “Do What You Want” made me audibly gasp.

Van Voorst Van Beest has long been my favorite stand-up player. His solo in “Kindness Is All” is especially interesting, sitting in the mix underneath Grover’s high-hat beat like playing with kids in the rain. He also stands out on “An Aspect of Things,” where the horns are just locked into each other for a number of many-note runs that belie they idea that jazz is just a bunch of improvisational messing around.

Austin blows the doors off his trumpet solo in the title track, getting angry and aggressive, pushing his instrument into places it doesn’t necessarily want to go. It pops you right in the face. Gaboury’s guitar work is mostly pretty measured — he has an elegant tone that can sometimes sound like a keyboard — but I love the way he provides sonic foundation for the crispness of the horn players.

Then there is, of course, Grover, who rides herd over the whole album, a force even when he’s being quiet. “Limbo” is one of the bigger head-nodders he’s ever written, just swinging and downright funky at times (in a way that doesn’t scream, “hey, look at me! I’m funky!”). Sometimes just the way Grover rolls his brushes around the snare, like on the opening to “A Sad Song Is Playing,” is lyrical and telling.

As his eighth album, Statement shows Grover is still growing as a composer and still having a hell of a lot of fun. Let’s hope there are many statements like this to come.