Cult of personalities

Rustic Overtones want you on their side

What’s the go-to motivational tactic used by every coach of an underdog team or demagogue looking to gain followers in a hurry? It’s us against them. Us against the world.

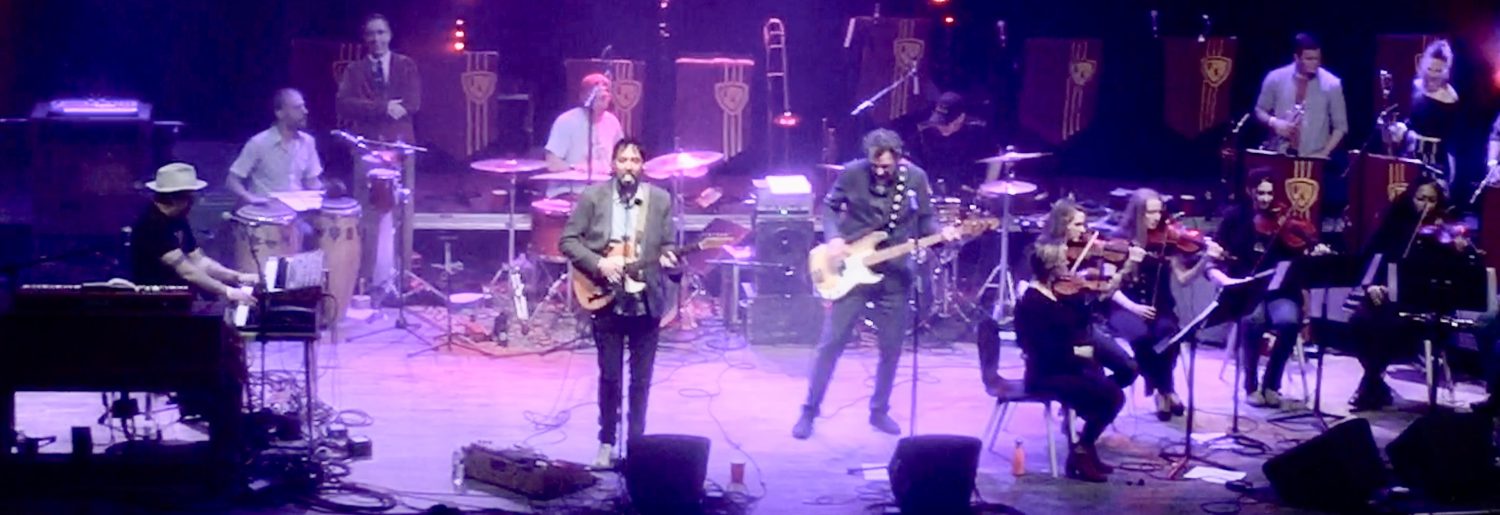

With Rustic Overtones’ eighth release, released in 2012, you’re either with them or against them. They don’t really care which. Let’s Start a Cult is everything their previous release, 2009’s New Way Out, wasn’t: All those string parts? Gone. The big and symphonic works that added up to an hour of music? This time they’ve stripped down to eight tunes and three minutes shy of a half hour. The guest players and revolving line up? With the addition of Gary Gemitti on drums and Mike Taylor on keyboards, they’re back to being the line-up you know and love: three horns, guitar, bass, drums, keyboard.

That doesn’t mean they’re back to hitting up-stroke ska songs and fire-breathing anthems, though. For this release, at least, they’ve gone much more organic, almost Edward Sharpe in their pop construction at times, and with a touch of lo-fi aesthetic that feels raw in a way they haven’t felt since before they were in the studio with Bowie.

It’s no mistake. “I like it gross,” Dave Gutter slinks on the devious “I Like it Low,” “I like the smell of cigarettes inside my clothes,” and there’s a baritone sax from Jason Ward that slithers through the weeds before being picked up by Ryan Zoidis’s tenor sax and a gritty trombone from Dave Noyes. The horns as a whole feel more part of this album than anything since before the hiatus – that you don’t really notice them is perhaps the best compliment I can pay to the arranging. They are wholly of the songs, rather than being ornaments.

“If there’s something you’re feeling inside, you should let yourself go.”

Oh, they’re tempting all right. “Let’s Start a Cult, Pt. 1” gets you right from the open with a poppy little flute line and digital hand claps and an “ooooh-oooh” bridge: “They can’t stop us all / How can they stop us all? / If we’re together.” They’ve embraced some new-school digital production here, too, integrating it so they manage to be space-age and ‘60s pop at the same time.

Just like they can combine old-time bluesy ballads with ‘80s sax lines in “Say Yes,” where Gutter knows how easy it can be to just join crowd: “It was hard to resist / They were pumping their fist / They were raising their flag in the distance.” His flittering guitar ain’t bad here either.

Gutter’s turned out some of his best lyrics in a while, too. The indie/big band “Solid” has this gem: “That’s not a halo, that’s a hole in your head / It’s not cold in the place that you go when you’re dead.” Ouch. It’s as mean as the low down Jon Roods bass that fuels the verse of “We’ll Get Right In” before it launched into melancholy pop for the chorus.

Remember? You’re with them, or you’re against them. And if you’re not with them? Well, as the ultra-dynamic album closer says, “fuck it / Let’s go out with a bang.”