Fire away

Pete Kilpatrick keeps the home fires burning

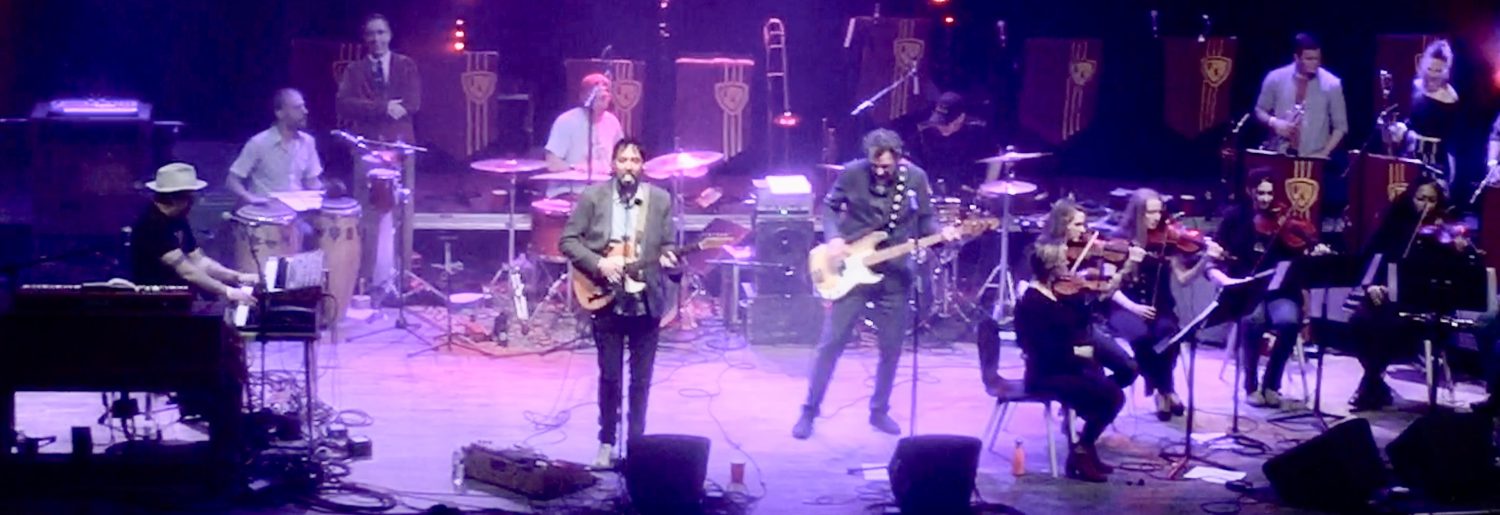

If anyone has grown up right in front of his fans, it’s Pete Kilpatrick. On the cusp of releasing his fifth full-length album (with an EP mixed in) and finishing out his first decade of performing professionally, Kilpatrick has gone from an impossibly winsome and charming, squeaky-clean young lad to, yes, a father, with a voice and sentiment both deepening along the way.

In the nearly four years since Hope in Our Hearts [this originally ran in March, 2012], Kilpatrick’s sound has grown immeasurably, gaining an important maturity and substance that has significantly augmented his already apt talent for pop-rock songwriting. With the brand-new Heavy Fire, not only does the band sound more weighty, layering in a bedrock of foundation that Kilpatrick’s vocals rest effortlessly on top of, but there is an undercurrent of introspection and the kind of examination of what’s important that comes with an infant squalling in the next room over.

In the nearly four years since Hope in Our Hearts [this originally ran in March, 2012], Kilpatrick’s sound has grown immeasurably, gaining an important maturity and substance that has significantly augmented his already apt talent for pop-rock songwriting. With the brand-new Heavy Fire, not only does the band sound more weighty, layering in a bedrock of foundation that Kilpatrick’s vocals rest effortlessly on top of, but there is an undercurrent of introspection and the kind of examination of what’s important that comes with an infant squalling in the next room over.

There is a steadfastness here, a comfort level, that allows for songs to take on pop airs, even to adopt some ’80s percussive techniques and dance on the edge of some light rock guitar tone from engineer/guitarist Pete Morse, without seeming inconsequential. This is helped immensely by Ed Dickhaut’s presence as resident drummer – he’s a force. An in-demand session drummer for years (he was on David Mallett’s Artist in Me, way back in 2003, I just noticed), here’s hoping he’s found a home for the foreseeable future, as his rhythms add a Paul Simon vibe to the record that are good enough to capture your attention all by themselves.

Dickhaut is complemented well, too, by vet bassist Matt Cosby, who’s subtle and easygoing and acts as the band’s center when so much can be swirling through each song. Morse and keyboardist Tyler Stanley (of Sly Chi and more) generally eschew traditional lead parts in exchange for phrases that interlock and intertwine and often make for a tightly controlled chaos of notes.

They echo the chaos of life’s unrelenting momentum forward, with which Kilpatrick seems determined to come to grips. The album is full of battle imagery, warring ideas and factions, but also at least four of his songs reference “home,” that place “where your heart is,” as we hear on the title track, or “where you left it,” or “what you make of it.” He is constantly exploring what the past has built, what the future holds, standing on the cusp of decisions that hold tremendous import.

In the excellent “Two Armies,” arranged in an orchestral manner, with Dickhaut rolling floor toms through the mix, we get a narrative of a “boy who lost his way.” What Kilpatrick has found over the course of the past few years, though, is some considerable range. I love how he reaches for the bottom in the chorus: “She said the past will set you free/ It’s just a glorified looking glass to me.” He’s added a bit of accent to his delivery, too, and improved his falsetto, now leaning toward Brit singers like Chris Martin or Keane’s Tom Chaplin.

“Hold Your Breath” opens like an Of Montreal or Yeasayer tune, with a cacophonous indie melody and a chorus of vocals, before settling down into what might actually be the most pop tune on the record, with the requisite sentiment: “All we’ll have is all we’ll ever need.” And “Martha” is the true ode, with a distorted keyboard tone contrasted with an ice-pick clean electric guitar: “Martha please don’t leave me/ I can’t afford to be alone/ This far from home.”

Funnily enough, the guitar solo of sorts in the bridge here reminds of Steely Dan’s “Reeling in the Years,” and it’s as though Kilpatrick is offering this record up as a demarcation. After this, he shall disavow all those childish things. He’s setting up shop. He’s through looking backward and has his sights set straight ahead with all of his burdens right up there on his back, a load he’s eager to carry.

He’s living, just like the track he opens the record with, the “American Dream.” He’s wise enough to intuit the answer when he asks, “Does anybody hear the words I say as I fall down?” No. You’re on your own kid. You’ve got it right when you notice later that “we’re all falling down.” And it sure is nice when we find someone who can pick us back up.

And they’re just getting started, really. Halo Sessions’ spare and measured arrangements weren’t necessarily by design. They were in some ways simply sketches by two vocalists, Dan Connor and Anna Lombard, who were trying to figure out just what kind of art they could make together. Over the past year they’ve decided they sound pretty great together, thanks, and they’ve collected themselves a band to fill things out: Max Cantlin (This Way) on guitar, Tyler Stanley (Sly-Chi) on keys, Colin Winsor (Jaye Drew and a Moving Train, Jason Spooner) on bass, Chris Dow (Band Beyond Description) on drums.

And they’re just getting started, really. Halo Sessions’ spare and measured arrangements weren’t necessarily by design. They were in some ways simply sketches by two vocalists, Dan Connor and Anna Lombard, who were trying to figure out just what kind of art they could make together. Over the past year they’ve decided they sound pretty great together, thanks, and they’ve collected themselves a band to fill things out: Max Cantlin (This Way) on guitar, Tyler Stanley (Sly-Chi) on keys, Colin Winsor (Jaye Drew and a Moving Train, Jason Spooner) on bass, Chris Dow (Band Beyond Description) on drums.